Mary (Wollstonecraft) Shelley is best known for her Gothic novel Frankenstein (first published in 1818). She was inspired by Lord Byron when he declaimed and sang The Tyrolese Song of Liberty by Thomas Moore. She was further inspired by Wordsworth’s sonnets to visit South Tyrol, where she bought a picture of Hofer in Brixen. She journeyed on up the PasseierTal to visit Hofer’s farmstead and guest-house. Her Rambles in Germany and Italy were first published in 1840.

Comparing Südtirol with Switzerland, she wrote: “There is something more sublime, more grand, more mysterious, in this Alpine region; which as far as I have seen, I infinitely prefer to Switzerland.“

Ultimately, though, she found the landscape oppressive and theatening: “I own I had no desire to linger longer in this land: we had continued for so many days among ravines, defiles, and narrow valleys, peering up at the sky from the depths of between mountains, that the eye grew weaker for a view of heaven, and yearned to behold a more extensive horizon.“

The first known guest book at Hofer’s Sandhof dates from 1835. According to an early German traveller’s report, the English were so eager to find Hofer souvenirs that everything at the Sandhof had to be hidden from them. But Hofer’s widow knew how to exploit the demand. Allegedly, she cut strips from an old flag that the people of the Passeier Valley took with them into battle, and sold them as trophies and souvenirs.

Such interest in Hofer relics had been generated by Maria Elisabeth Budden’s 1833 report:

“As chief and director of these valiant bands, the name of Hofer is handed down to posterity in the annals of fame. Just when his country needed a guiding head and valiant arm, this hero started from his humble rank to rally the patriotic sons of Tyrol!“

Another woman, the poetess Louisa Stuart Costello, picks up the cause in 1846:

“ ‘Tis, as Hofer’s spirit woke,

he whose rifle freed the vales,

And in wailing accents spoke,

telling old, remembered tales.

Of the peasant hero’s fate,

Brief success and ceaseless fame,

England’s succour, all too late!

France’s vengeance, and her shame.“

Travel literature was influenced by all these works, with hardly any travelogue before the 1850s able to avoid the myth of the hero in the struggle for freedom. English-travel writers especially defined the historical and political image of Tyrol. The story of Andreas Hofer became the story of the desire for freedom of a people rising against tyranny.

After the initial euphoria, travel literature began in the second half of the 19thc. to describe the figure of Hofer in a more reserved and even critical manner, representing him as a complex personality containing both strengths and weaknesses. The depictions of the rebellion in travel literature and travel guides contributed to the myth from which the Tyrolean tourist industry has been profiting ever since: Tyrol became ‘Hofer Land‘.

John Murray’s 1855 Handbook for Travellers in Southern Germany looks in a more balanced way at Hofer the man.

“(Hofer) was naturally of a good-natured and kind disposition, and no act of wanton cruelty has been attributed to him during his whole career. (…) But his rashness on some occasions, and his weakness and indecision on others, were highly injurious to himself and the cause he espoused.“

Also published in 1855, ‘On Foot through Tyrol“ by Walter White reads as follows:-

“Hofer, the Tell of Tyrol, is a hero about whom there is nothing mythical, as with his forerunner in Switzerland.“

He talks about how the “Passeyrthal is classic ground. Every step brought me to the birthplace of Hofer.“

He continues:

“The struggle for freedom in 1809, with its fierce enthusiasm and heroic incidents, its triumphs and disasters, appeals strongly to the sympathies of all who hold liberty as their birthright. Let us, while pacing slowly along the banks of the darkening river, recall a few passages to memory.“

And he proceeds for several pages to retell the heroic struggle by referring to actual locations he has visited.

Turning to the fictional narratives written in 19th c. Britain, we need to pay tribute here to the pioneering research work carried by the late Professor Harro Heinz Kühnelt, former Professor of English Literature at the University of Innsbruck. He analyzed closely the historical novels about 1809: in particular

Firstly,

Hofer, The Tyrolese, by Elisabeth Thomas (1824), where we read:

“…respected for his piety, his honesty and his loyalty…Hofer proved himself a man of singular modesty and humility…Wherever he appeared, the work of spoliation was stayed – whenever he spoke, his bidding was obeyed.“

Secondly,

The Year Nine: A Tale of the Tyrol, by Anne Manning (1858), which states:

“…Hofer had never endeavoured to ape a grandeur that he had not; he was a plain, simple, upright man from first to last. He had attained a great, though brief power, and had not abused it: he had fallen of it, but not into despair.“

And, thirdly,

The Tyrolese Patriots of 1809, by Diana Thompson (1859), which asserts:

“Never was a patriot moved by a purer and more disinterested love of his faith and of his fatherland.“

When we turn to early 20thc. travel literature about the Tyrol, we find Hofer is now almost mythologized.

“…Hofer: a village publican against the world“ (according to Joy of Tyrol, by J.M. Blake, 1905)

“…the redoubtable Andreas Hofer, taken prisoner through gross treachery, was in his captors‘ eyes a hero too dangerously popular to be left alive. He died the death of a brave man, standing erect and profound before the firing file, himself giving the word of command that ended a career of which the Tyrolese have every right to be proud.“ (In The Land in the Mountains, by W.A. Baillie-Grohman, published in 1907)

In another English travel guide, of 1908, we read: “(Hofer’s) memory is kept green throughout the country, and Meran has of late taken to producing a play in which self-taught peasant actors manage to bring the principal scenes of the country’s heroic resistance vividly before the onlooker.“

The doyen commentator of inter-war Austria is G.E. R. Geyde, the former Times correspondent for Central Europe. In his A Wayfarer in Austria (1928) he draws on his journalistic experience:

“The Austrian Emperor gave the hand of his daughter to Napoleon; the Archbishop of Vienna anointed the bride with the same sacred oil with which he had consecrated the banners of 1809; the servile Press which narrated the wedding festivities found no space to mention that the Emperor’s bravest subject, the Tyrolese leader, Hofer, was executed by Napoleon (sic!) as a brigand in the interval between the (marriage) contract and the celebration of the (wedding).“

Geyde’s original 1928 book was later expanded to become Introducing Austria, published in 1955.

By contrast, J.D. Newth’s romanticised account (1931), beatifully illustrated by the great Alpine artist Compton, rhapsodizes about…

“…the unremitting tiller of the soil upon whom ultimately all society still depends, the sturdy independent character of whom Andreas Hofer is the type, the peasant proprietor whose hard self-supporting life is the most manly and the least selfish of any, the source of fresh blood for the towns and factories. These extremes of his good and bad qualities are all to be traced in the first instance to the overwhelming influence of environment, to the rigour of lonely mountain life.“

Speculative words. A similar theme is picked up by F.S. Smythe in Over Tyrolese Hills (1936):

“In Tyrol there are (many) whom Andreas Hofer led to victory against tyranny and oppression…, independent folk who cherish their liberties as they cherish their very existence. These, and not the political intellectuals of the towns, are the backbone of Austrian freedom and independence.“

1936: difficult times politically for Austria. Spongy, spineless Austria needing such a ‘backbone‘?

Also published in 1936 is Nina Murdoch’s Tyrolean June.

She describes Hofer as:

“The sturdy Sandwirt, wearing the green jacket and broad-brimmed hat of the Passeiertal peasant.“

She retells the story of Britain’s financial support of the Tyrolean cause.

“In that desperate struggle of 1809 was born the extremely friendly feeling of the Tyrolese for the English. For in September 1809, when it was clear that Austrian support was not going to be as reliable as they had expected it to be, a wine-merchant of Innsbruck and an innkeeper of Vorarlberg set off on a journey which seemed almost more adventurous than fighting against the invader, since it involved not only a passage through foreign lands but putting to sea in a ship. The Tyrolese had decided to ask England for financial help and it took the two deputies a month and four days to accomplish the journey. They arrived in London on October 24. Johann Georg Schennacher and Joseph Christian Muller were received at the court of George III, complimented on Tyrol’s brave fight for liberty and granted a subsidy of 30,000 Pounds. Although it proved to be too late to turn the tide in their favour, the Tyrolese remember still the sympathetic gesture.“

Whatever happened to that 30,000 Pounds, a very substantial sum at the time, one might well ask.

Guide books in the second half of the 20thc., on the whole, do not tend so much to give Hofer full prominence as a hero. The 1809 uprising is now looked at with greater critical distance and sharper perspective. The term ‚uprising‘, of course, begs a question. Which other terms come into play here? The simple word ‚rising‘ itself, in comparison with ‘uprising‘ , ‘insurgence‘, ‘ insurrection‘, ‘rebellion‘, ‘revolt‘, …? From which perspective do we use any of these terms?

Monk Gibbon (1953) goes for the term ‘resistance‘. He also – sadly – reverts to tourist cliches:

“It is the spirit of the mountains, the spirit of the Tyrol, of Andreas Hofer, of all that is unsubdued and unsubduable. Though it is mountain virtue, the plain-dwellers (those living down in the valley and on the flatlands) are convinced that they have a share in it. They think of themselves in terms of leather trousers and shoe slappings.“

He goes on to dramatize Hofer’s final minutes:

“Hofer, with unbandaged eyes, faced the firing squad. ….. His final words are to my mind tragically bitter ones: ‘Farewell, vile world! Death in my eyes is not worth a single tear‘. …. Hofer is the symbol of peasant courage and peasant virtue.“

Richard Rickett’s 1966 Survey of Austrian History refers at some length to Tyrol’s ‘fight for freedom’ under Hofer:

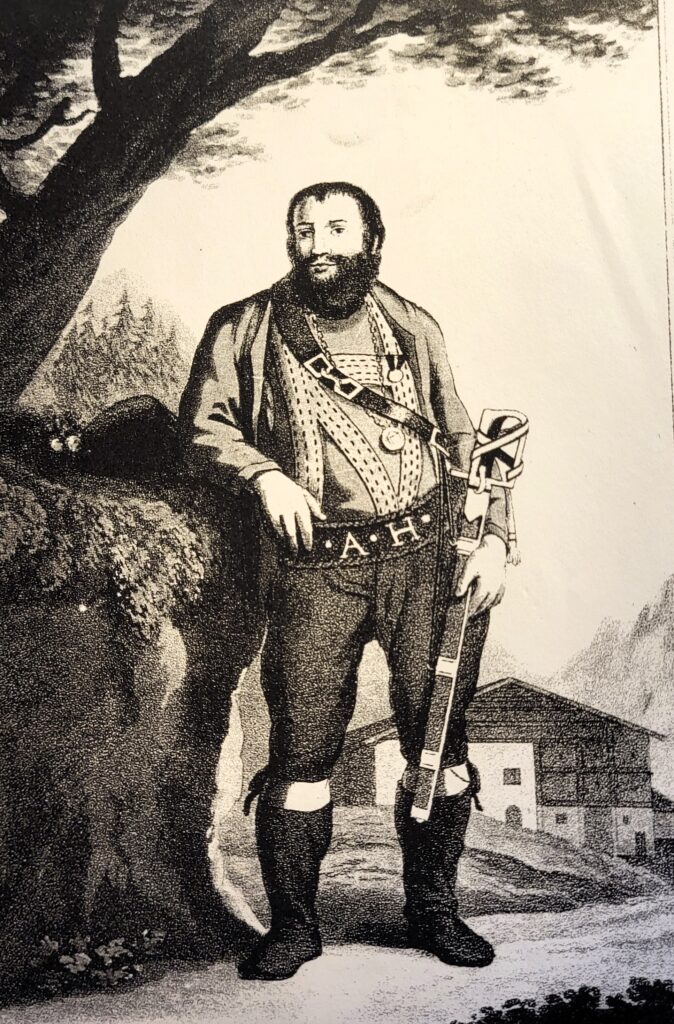

“In January 1809 Hofer, with his colleagues Huber and Nessing, wound their secretive way to Vienna. It was of course essential that their presence in the capital should be kept as secret as possible, which – in view of Hofer’s striking appearance – with his great black beard and his Tyrolese national costume, was no easy matter.“

Later he continues: “Through a series of heroic battles in 1809, this annus mirabilis, Tyrol had liberated itself by her (sic!) own exertions, without the Imperial Austrian forces making any appreciable contribution to the victory.“

After the engagement at Wörgl, Rickett adds: “the full brunt of the struggle had to be borne by the Tyolese peasants, armed as often as not with scythes and billhooks and other agricultural implements. One worthy is said to have brandished a heavy wooden crucifix studded with nails.“

His assessment of Hofer the man is, on the one hand, relatively balanced.

“It was at this juncture that Andreas Hofer’s stature grew from that of a local leader of the volunteer contingent from the Passeier Valley to that of a unanimously acclaimed leader of the whole people. After the pitiable failure of the Imperial Austrian troops and their leaders, Hofer was approached by well-known personages from all parts of the Province, imploring him in this hour of need to take the defence of the Tyrol into his own hands. Andreas Hofer had never aspired to leadership; it was thrust upon him by the people, who placed the fullest confidence in him.“

But Rickett’s description of Hofer the man reads with almost romantic pathos: “His outward appearance was certainly impressive; he was tall and massive in frame, with a great black beard which gave him an appearance of dignity far beyond his years, and he always wore the traditional costume of his native valley. “

“In this year of destiny Hofer was in his 42nd year. What won the complete confidence of the peasants was simply and solely Hofer’s character: they obeyed him, they followed his instructions, and it was due entirely to his moderation and leniency that the uprising never degenerated into an exchange of atrocities. Clumsy in bureaucratic matters, when it came to choosing a position or fomulating a plan for throwing the invader back across the frontiers, Hofer showed his inborn instinct for turning the mountains to the best possible advantage by the use of previously prepared avalanches.“

Where Rickett is insightful, I think, is concerning Hofer’s possible psychology later. Before the final battle of Berg Isel, Rickett argues: “(Hofer was) in a mood of abject resignation, tortured by doubts and anxieties, without any plan or purpose.“

However, he reverts to romantic mode and reaches a crescendo of rhetorical question when he writes:

“Hofer’s behaviour during the last weeks of the uprising can only be explained by a tragic mental confusion from which he could find no way out. With the final general collapse of 1809 Hofer must have lost all confidence in himself. How could a simple, right-thinking, unassuming peasant comprehend that his Emperor, in whose name he had issued so many orders, endured so many hardships and undertaken so much responsibility, for whose throne he had led so many of his compatriots to death on the battlefield, his Emperor who had solemnly promised never to consent to the separation of Tyrol and who only a few weeks previously had rewarded him with a medal of honour, could be capable of breaking his word? This was the tragedy in which Hofer was caught up, and which eventually led him in desperation to the final, senseless act of resistance.“

The rest – as they say – is history…!

Richard Bassett’s controversial 1988 book, The Austrians, is distinctly provocative:

“Tyrol’s irrepressible spirit of independence and heroism“ is embodied by Hofer, „the Alpine Austrian’s hero par excellence.“ “The tombs of Hofer and his lieutenants are a permanent symbol of defiance and Tyrol’s contempt for distant Vienna.“

Turning to contemporary travel guides to Austria, the Blue Guide, by Ian Robertson, 1992, calls Hofer “ the Tyrolese patriot who commanded the gallant skirmishing of Tyrolean marksmen (Schützen).“

In 1996 Gordon Brook-Shepherd summarizes the story in compact terms: “Andreas Hofer, the innkeeper from the Passeier Valley, is the supreme example of regional resistance. …. (His) shabby fate (executed in Mantua in 1809, on charges of treason) only strengthened the Tyroleans‘ fierce provincial pride.“

The current Rough Guide to Austria – a very down-to-earth travel guide – introduces Andreas Hofer as a “local patriot…with a ready-made army who led a revolt against the Bavarians and their French backers. Subsequently dubbed the ‘Tyrolean War of Independence‘, this heroic but doomed escapade was launched with the encouragement of a Viennese court that had no real intention of providing military support. The Tyroleans were left to fight alone and Andreas Hofer was shot by the French in 1810.“

By using such almost dismissive terms, the Rough Guide plays down the significance of Hofer’s revolt. Indeed, it could be seen as an attempt to off-set the over-enthusiastic and romanticised accounts that spread almost immediately after his death and through much oft he 19thc.. In short, an attempt to de-mythologize him.

The latest British publication, 2006, A Concise History of Austria by Steven Beller, offers a cold, sobering , prosaic assessment:

“The Tyrolean rebellion, designed by Johann and Hormayr to coincide with the Austrian war effort, was led by Andreas Hofer to remarkable success against overwhelming odds. Hofer’s campaign against Bavarian and French forces, and the … Tyrolean victories at Bergisel over the spring and summer of 1809, have become part of Tyrolean (and Austrian) legend. By the fourth Bergisel battle in August, however, the Tyroleans were fighting without Austrian support, and by November 1, when the French and Bavarians finally won, Austria had already made peace. The most Austria could do by then was to plead for amnesty for the rebels, and it was a mere spectator when Hofer’s ill-advised further resistance led to his execution in Mantua on 20 February 1810.“

So, terrorist or freedom fighter, this Andreas Hofer? British perceptions of him and 1809 seem to have gradually changed over the last 200 years – from heroic idealization in the first half of the 19th.centrury via a more critical evaluation of his character, with both virtues and faults, towards mythologization in the early 20thc.

Nowadays, in an age which deconstructs myths, which de-mythologizes heroes, it seems 1809 is largely regarded as a fated cause, a betrayed enterprise, led by a patriotic innkeeper, one Andreas Hofer, a complex, ambivalent figure. As far as 1809 as a whole is concerned, the Habsburgs applauded the uprising, but shied away from offering concrete support. Finally, the revolt simply petered out…

von

von