POETRY CAFÉ Special / Wednesday June 18, 2025: 14.00 – 14.30

Good afternoon!

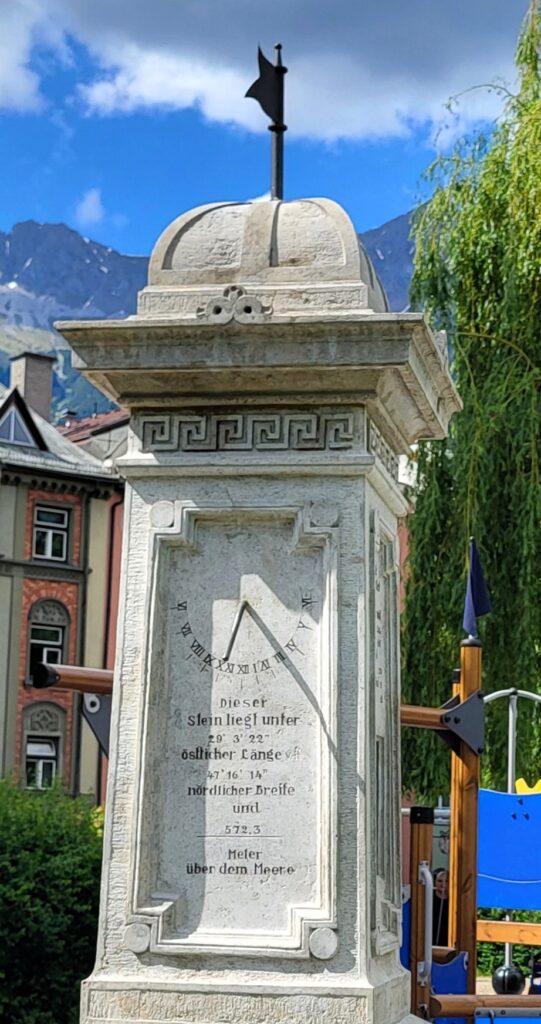

This is Sandra – (and Andrew ) – Milne-Skinner here in the Walther Park, Innsbruck, overlooking the River Inn.

We’ve been running a regular programme for Freirad for twelve years now. It’s called Poetry Café, and it’s in English. We’ve notched up 209 Poetry Café programmes since 2013.

(Photo: private)

ccc

ccc

What is ‘Poetry Café’?

We take a theme, a topic, and put together a programme of several poems or poetic prose on that theme or topic. We intersperse the poems with several pieces of music to evoke or underline the topic.

Today we’re offering this one-off, 30-minute programme from the Walther Park.

Why are we broadcasting live from the ‘Walther von der Vogelweide Park’? Why is this park called this?

Well, this park lies between the Innstrasse and the Innallee, in the district of Sankt Nikolaus. The ‘Waltherpark’ was laid out between 1875 and 1876….at a time when Innsbruck was being re-designed, with many new buildings being added. Earlier this park area would have been where boats, barges and rafts would have docked. The river was the main channel for trading – the roads being poor.

The monument to the medieval poet Walther von der Vogelweide was erected in 1876. It is not known that Walther had any direct relationship with the ‘fortified bridge-town on the Inn’, which is what Innsbruck originally was. Certainly, Walther was the greatest lyric poet in German of the Middle Ages!

Walther von der Vogelweide

(* approx. 1170, † approx. 1230)

ccc

So, who exactly was Walther von der Vogelweide? He seems to have been born about 1170. We know he dies in 1230. He looked on Austria as his native home: “Ze Osterriche lernte ich singen und sagen” – ‘In Austria I learnt how to sing and make statements’. In a Heidelberg manuscript we have a later image of the poet sitting on a stone, cross-legged, with his left hand under his chin supporting his tilted head: in short, he’s in the classic ‘thinker-pose’. Think of Rodin’s sculpture!

“Ich saz uf eime steine/ und dahte, bein mit beine”

In English:

“I sat down on a stone,/ and crossed my legs and set my elbows on them./ I rested my chin and cheek in my hand./ Then I pondered very earnestly/ how one ought to live one’s life on earth./ I could not find any solution to the problem of three things:/ gaining a good reputation, having worldly possessions, and – most importantly – attaining God’s grace./

As a medieval ‘Minnesänger’, Walther celebrated courtly love (‘hohe Minne’), but such love for an unattainable lady had to remain unrequited, unfulfilled. As compensation for such sexual frustration, there was also ‘niedere Minne’. Here physical love could be celebrated with a young woman of lower rank!

‘Under der linden an der heide’ expresses such love on the part of the woman. First, let’s hear an English translation:

“Under the lime-tree by the common, where we two had our bed, you can find flowers and grass both neatly picked. At the edge of the forest, in the dell, Tandaradei, the nightingale sang so sweetly./

I came to the meadow, to find my sweetheart was already there. There I was received with the words ‘Noble Lady!’ I shall always be happy to think of it. Did he kiss me? I should think about a thousand times! Tandaradei! See how red my mouth is!/

I saw that he had made a lovely bed out of flowers. Anybody who comes by that way will give a knowing smile; he can see from the roses where my head lay./

If anyone were to know – God forbid they should – that he lay with me, I would be ashamed. I hope that no one will ever find out what he did to me, except us two and a little bird –Tandaradei – but then it can keep a secret./”

Here’s the original text, in Middle High German, set to a French Trouvѐre melody En Mai, In May.

1. CD Tr. 8 Under der linden an der heide… 3‘ 13 secs

That was ‘Under der linden an der heide‘ by Walther von der Vogelweide, performed there by the Ensemble für Frühe Musik Augsburg.

A wonderful celebration of mutual physical love, of a gentle lay together on the grass. But we’re not sure the Walther Park here is private enough for that!

Walther spent his early career as a professional poet at the court of Vienna, but was then forced to leave. He then wandered unhappily from one court to another. He supported the Hohenstaufens and was rewarded by Emperor Frederick II. He also wrote moral and political poetry in the form of ‘Sprüche’, or telling statements. He wrote about the spiritual value of the Crusade to the Holy Land, to win back Jerusalem for Christianity. Walther may have visited the Holy Land with the crusading Emperor Frederick II.

We’re going to hear the ‘Palästinalied’, the Palestine Song, by Walther.

Here’s the text in English translation:

“From the moment my sinful eye/ looked on this noble land, which is so widely praised/ I have been living in a noble manner/ for the first time in my life./ What I have always wanted has come about/ for I have the place where God walked in the flesh./

O Holy Land, you are the richest, noblest and most beautiful/ of all the rich, beautiful and noble lands I have ever seen./ How many miracles have taken place here!/ A maiden bore a child, Lord over all the hosts of angels./ Was that not a perfect miracle?”

And now the original melody. In fact, the ‘Palästinalied’ is the only work of Walther for which the original melody has been preserved. This is from the late 12thcentury!

2. CD Tr. 8 Allerest lebe ich mir werde… (Palästinalied) 3‘ 16 secs

That was the ‘Palästinalied’ by Walther von der Vogelweide. It was played there in a 1971 recording by the Early Music Consort of London under the late, great David Munro.

This is Poetry Café, with Sandra – and Andrew – Milne-Skinner. Today we’re doing a one-off programme from the Walther Park in Innsbruck on the medieval poet Walther von der Vogelweide and an early Renaissance artist ….

A Quiz Question! Who sketched and completed a watercolour from this side of the River Inn, from almost this very spot, probably in 1494?

Answer: Albrecht Dürer

You may well know Dürer’s famous watercolour of Innsbruck viewed from the North, from this side of the River Inn. It’s now in the Albertina, Vienna, along with his famous study of a hare.

Dürer’s Innsbruck seems to float like an island on the River Inn, rather like Venice on the lagoon. In fact, Dürer probably did the watercolour on his return from Venice!

In the summer of 1494, the 23-year-old Albrecht Dürer left Nürnberg in Germany for Italy – probably because of a threatening outbreak of plague. He left behind … Agnes Frey, the woman he had just married!

It would have taken Dürer some 3 weeks to make the journey from Nürnberg via Augsburg and Innsbruck to Venice. He may well have dropped down into the Inn Valley from Mittenwald via Scharnitz and Mösern. Did he stop perhaps at the Mellaunerhof at Oberpettnau, , between Telfs and Zirl, we wonder?

(By the way, that historic coaching inn and Gasthaus is re-opening this autumn, under new management yet again! We have happy memories from years ago of having a meal in the Rittersaal of the Mellaunerhof, eating off pewter – that is, early tin – plates!)

It’s possible that Dürer stayed a few days that summer of 1494 in Innsbruck with a relative of his wife’s, by name Peter Rummel.

We’ve got a copy of Dürer’s watercolour of Innsbruck here in front of us! The original is some 12 by 18 centimetres. The word ‘Isprug’ –spelt ‘I-s-p-r-u-g’ – is in the top right corner. What’s surprising, perhaps, is the topographical accuracy. We can easily identify the Ottoburg, as well as the snow-covered Patscherkofel – the rounded rear over Innsbruck – and the Glunguzer. The time of year seems to be late winter or early spring. The reflections on the water and the various light effects might be the result of Dürer’s visual experiences in Italy. Was he experimenting with water-colour for the first time? Is this a study in atmospheric effects? A private document for him to use later? Or is this simply a traveller’s souvenir en passant Innsbruck, in passing by our town? The towers and battlements of Innsbruck certainly look ‘picturesque’!

Dürer returned to Nürnberg via Innsbruck , in the spring of 1495. Was it then that he first sketched or actually completed the watercolour? Or did he leave it until later, in Nürnberg?

This watercolour of Innsbruck is one of the earliest landscape watercolours in Western art! Dürer made some 32 watercolours of landscape, as well as studies of trees and cliffs.

The Upper Inn Valley from Telfs westward seems to feature in the background to Dürer’s 1498 Self-Portrait, the one in the Prado of Madrid. The open window certainly shows an Alpine landscape with a river. Some 20 years ago it was claimed that the background scene was the River Inn seen from Mösern, above Telfs. If you’re interested in this theory, then go up to Mösern, and look up the Upper Inn Valley.

The Prado Self-Portrait by Dürer shows him as an elegant, refined Venetian artist. He is extravagantly dressed in the latest Venetian fashion, with a rakish cap over his cascading curls of hair. A Venetian dandy, then, showing that he has travelled across the Alps to learn from Italy and its artists. While in Italy, Dürer was clearly influenced by the work of Mantegna and Bellini, as well as by the science of perspective. Is the Alpine scene put in to show off his newly gained knowledge of landscape perspective?

When we moved into our new house in Inzing, we started a Guest-Book for all our many visitors. An early entry was by our good friends, Pete and Susie Street. Pete also happens to be a watercolourist! When we talked about the Dürer watercolour of Innsbruck, he was happy to come down to Innsbruck, to the Walther Park here, and actually do a watercolour of the other side of the Inn from as close a position as possible to Dürer’s! The brilliant end-result graces our Inzing Guest-Book!

Another famous traveller who came down from Mittenwald via Mösern and Zirl to Innsbruck, en route for Italy, in 1786 was…..yes……Johann Wolfgang Goethe!

This is how he describes his trip down into the Inn Valley in his ‘Italienische Reise’, Italian Journey’, in English:

“Near Scharnitz one enters the Tirol. At the frontier the valley is closed in by a rock wall which joins the mountains on both sides. On one side the cliff is fortified, on the other it rises perpendicularly. It is a fine sight. After Seefeld the road becomes more and more interesting. ….

Now I looked down from a ridge, into the valley of the Inn, and saw Inzing lying below me. The sun was high in the heavens and shone so hotly that I had to take off some of my outer garments. Because of the ever-varying temperature, I have to make several changes of clothing during the course of the day.

Near Zirl we began to descend into the Inn Valley. The landscape is of an indescribable beauty, which was enhanced by a sunny haze. The postilion hurried faster than I wished,… so we rattled downhill beside the Inn and past St. Martin’s Wall, a huge, sheer limestone crag. I would have trusted myself to reach the sport where the Emperor Maximilian is said to have lost his way and to have come down safely without the help of an angel, though I must admit it would have been a reckless thing to do.

Innsbruck is superbly situated in a wide fertile valley between cliffs and mountain ranges.”

We certainly agree with Goethe, more than 200 years later!

But it’s time to leave Innsbruck…

Heinrich Isaac was a Flemish composer at Emperor Maximilian’s court at Innsbruck in the 1490s, the same period as when Dürer passed through. Isaac’s ‘Innsbruck, Ich muss dich lassen’ is well known, and is often sung at the end of an Early Music concert.

The text in English translation runs:

“Innsbruck, I must leave you./ I am on my way to foreign parts./ My joy is taken from me/ And I know not where I shall find it/ When I am in misery.

Now I must suffer greatly/ And can only confide in my dearest love./ My love, now take pity in your heart/ On wretched me, because I must away.

My comfort above all other women,/ I shall always be yours,/ Always faithful, and honouring you./ May the Lord protect you now/ And preserve your virtue/ Until I return.”

3. CD Tr. 12 Heinrich Isaac (c.1450-1517): Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen 3‘ 28 secs

That was ‚Innsbruck, Ich muss dich lassen‘ by Heinrich Isaac. It was performed there by the Kammerchor Walther von der Vogelweide, under their founder Othmar Costa, now sadly missed. That song became the ‘hymn’ of that marvellous, Innsbruck-based choir.

It’s always interesting to compare interpretations of Early Music.

So, to sound out, here’s Isaac’s ‘Innsbruck, Ich muss dich lassen’ in another recording, this time by the Early Music Consort, under David Munro.

Thank you for your company. Thank you for listening.

4. CD Tr. 10 Isaac: ‘Innsbruck, Ich muss dich lassen’ 3 mins 14 secs (FADE OUT….)

Fotos: L. Strasser

von

von