What makes a so-called‚ hero ‚ into a genuine, respected, even immortal hero? And almost a myth? But, ultimately, a myth to be deconstructed. A figure to be de-mythologized.

Let us look at the British reception of Hofer.

In general terms, Andreas Hofer stands for a love of freedom and fatherland, linked with a loyalty to Emperor, faith in God and moral integrity. The Hofer type is also the personification of the image of the ‘noble savage‘ set out by Jean Jacques Rousseau in the mid-18th.c.: men who, in their mountains, have not yet come into contact with corrupt, degenerate political society.

Since Rousseau made his ‘back to Nature‘ call, travellers from all over Europe, and especially from Britain, have looked in the midst of the mountains of Tyrol for the sort of people Hofer personifies.

The native Tyroleans, both north and south of the Brenner, have at the same time both internalized and projected that image, raising Hofer to almost mythic proportions.

Tyrol became known through the figure of Hofer. Travel and tourism also grew on this account throughout the 19th.c.

The theme of Hofer’s heroism and the 1809 uprising were picked up early in England, already at war in Spain and Portugal at this time. Britain was keen to open up a second front against Napoleon, and so the British Government finally offered financial help to the Tyrolean cause.

Some 11,000 Florins were earmarked for Hofer’s cause in Tirol, a substantial part of the 30,000 Pounds granted to the Austrian cause…but, alas! The money came too late!

The Romantic poet of Nature, William Wordsworth, was one of the first to pick up the Tyrolean cause. Originally, he was politically engaged and even travelled to France again in November 1791 to witness revolutionary fervour in Paris for himself. (Incidentally, he had a love affair with an Annette Vallon, by whom he had a daughter.) In February 1793 War was declared between England and France. The violence of the French Terror (1793-4) showed Wordsworth how revolutionary action could betray humane motives. After Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor in 1804, Wordsworth became more disenchanted, disillusioned even, feeling republican ideals had also been betrayed.

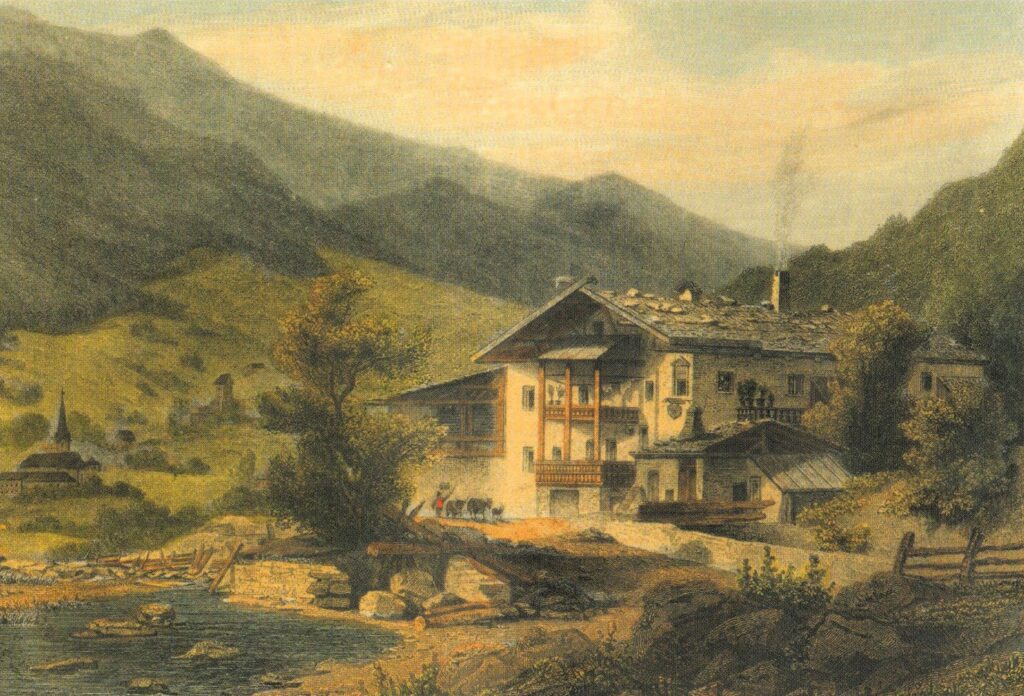

Der Sandhof, Geburts- und Wohnhaus von A. Hofer – Stich um 1850 / © MuseumPasseier

©Wordsworth’s early republican radicalism emerges clearly in the “Advertisement to Lyrical Ballads, with Pastoral and Other Poems“ (1798). The Preface proclaims that, at moments of crisis – like the French Revolution and the threat of Napoleonic France – the poet is defender of human nature with its ideals. Wordsworth was clearly carried away by the abstract ideas of liberty and equality and wanted to experience them for himself in real terms.

“All good poetry“, he claims, “is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling“. Even so, he later described his own poetic process as “emotion recollected in tranquillity“.

Between the autumn of 1809 and the spring of 1810 he wrote 4 sonnets about Hofer and the Tyrolean uprising for the London magazine The Friend. They are now collected and edited within the section “Sonnets Dedicated to Liberty“ (OUP). One poem, published on Oct 26 1809, celebrates the figure of Hofer himself.

In German translation:

Ist der Held von sterblichen Eltern geboren, durch den die unerschrockenen Tiroler geführt werden? Oder ist es Wilhelm Tells grosser Geist, der von den Toten zurückgekehrt ist, um einem verlorenen Zeitalter neues Leben zu verleihen?

The original English:

“Of mortal parents is the Hero born

By whom the undaunted Tyrolese are led?

Or is it Tell’s great Spirit, from the dead

Returned to animate an age forlorn?

…

A further sonnet entitled “On the Final Submission of the Tyrolese“, published on Dec 21 1809 in The Friend, asserts and commands:

It was a moral end for which they fought;

…

Advance – come forth from thy Tyrolean ground,

Dear Liberty! Stern Nymph of soul untamed;

Sweet Nymph, O rightly of the mountains named!

Through the long chain of Alps from mound to mound.“

His poems, direct and forthright, were read in the noble clubs of London at the height of the Napoleonic Wars. His assessment of how the Tyrolean cause was betrayed is damning and was to resonate in political circles through the 19thc.

“Austria a Daughter of her Throne hath sold!

And her Tyrolean Champion we behold

Murdered, like one by shipwreck cast,

Murdered without relief.“

As a result, the Tyrolean cause received strong, sympathetic support in Britain. Several books on Hofer were soon published in Britain. ‘Alpine’ music became popular.

Josef Freiherr von Hormayr’s Geschichte Andreas Hofers, published in Leipzig in 1817, although rather partisan and self-centred, a one-sided witness in short, was widely read and partly translated into English.

But it was Charles Henry Hall’s 1820 biography Memoirs of the Life of Andrew Hofer that really stirred the British imagination. It was then re-edited in 1822 and became the standard biography in the first half of the 19th. Century.

In 1828 Das Trauerspiel in Tyrol, a play by Karl Leberecht Immermann, was received favourably when performed in London. The play formed the basis of the opera Andreas Hofer by Albert Lortzing.

1830 saw Rossini’s music to his opera Guillaume Tell being adapted for a successful musical production of a dramatic text by James Robinson Planche. The influence of Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell resonates on:

„Wenn der Gedrückte nirgends Recht kann finden,

Wenn unerträglich wird die Last – greift er

Hinauf getrosten Mutes in den Himmel

Und holt herunter seine ew‘gen Rechte,

Die droben hangen unveräusserlich

Und unzerbrechlich wie die Sterne selbst.“

Walter Savage Landor wrote in 1832:

“The name of Andreas Hofer will be honoured by posterity far above any of the present age.“

Timeless, eternal star status, then!

Three Scotsmen, all too conscious of Scotland’s brave struggle for independence from England through William Wallace (‘Braveheart‘) and Robert the Bruce in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, contributed a great deal to memorializing Andreas Hofer in Britain, and – ultimately- in Europe.

Walter Scott, renowned then in Europe and the author of Rob Roy (published in 1817) – the historical novel about a rebellious 18th.c. cattle-trader and clan chief – wrote in 1827:

“The defence of the Tyrol (…) fills a page in History as heroic as that which records the exploits of Wilhelm Tell.“

Again we have this explicit comparison with the Swiss hero.

In 1830 another Scotsman Henry David Inglis (1795-1835) travelled through Bavaria and Tyrol. A year later he published ‘The Tyrol with a Glance at Bavaria’. He observed that there was “much genuine piety“ in Tyrol. “Where ever morals are pure, true religion is well rooted, and widely diffused; and judging by this test, such we may conclude of the Tyrol.“

And he continues:

“The Tyrolean is just, and honest, not only because to be just is a duty enjoyed by religion; but because he is a Tyrolean; and it is the character of Tyroleans to be just and honest. Married men and women are faithful, and the girls are chaste, because they are Tyroleans; and fidelity and chastity are Tyrolean virtues.“

In 1832 yet another Scotsman, Leitch Ritchie, wrote about 1809 in his Travelling Sketches:-

“…a struggle, the result of which brands with eternal dishonour the name of Austria. We trust that, on the next emergency, she will call in vain on the brave peasants of the Tyrol; whom she first said to be an enemy – then tempted into rebellion – and then betrayed and abandoned.“

Harsh, direct words, indeed. But apparently very close to the truth.

It is extraordinary that so many Scottish writers were interested in Andreas Hofer. We may speculate why! Both Scotland and Tyrol have ‘common ground’ (so to speak!): both highland, mountainous regions. Both Scots and Tyrolese have a strong sense of independence. Both are resilient and resourceful.

Having lived in Tyrol since 1972, I write both as a Tyrolean Scot and as a Scottish Tyrolean!

How did British travellers and writers regard Andreas Hofer in the second half of the 19thc., and beyond?

Mary (Wollstonecraft) Shelley is best known for her Gothic novel Frankenstein (first published in 1818). She was inspired by Lord Byron when he declaimed and sang The Tyrolese Song of Liberty by Thomas Moore. She was further inspired by Wordsworth’s sonnets to visit South Tyrol, where she bought a picture of Hofer in Brixen. She journeyed on up the PasseierTal to visit Hofer’s farmstead and guest-house. Her Rambles in Germany and Italy were first published in 1840.

Comparing Südtirol with Switzerland, she wrote:

“There is something more sublime, more grand, more mysterious, in this Alpine region; which as far as I have seen, I infinitely prefer to Switzerland.“

Ultimately, though, she found the landscape oppressive and theatening:

“I own I had no desire to linger longer in this land: we had continued for so many days among ravines, defiles, and narrow valleys, peering up at the sky from the depths of between mountains, that the eye grew weaker for a view of heaven, and yearned to behold a more extensive horizon.“

The first known guest book at Hofer’s Sandhof dates from 1835. According to an early German traveller’s report, the English were so eager to find Hofer souvenirs that everything at the Sandhof had to be hidden from them. But Hofer’s widow knew how to exploit the demand. Allegedly, she cut strips from an old flag that the people of the Passeier Valley took with them into battle, and sold them as trophies and souvenirs.

Such interest in Hofer relics had been generated by Maria Elisabeth Budden’s 1833 report:

“As chief and director of these valiant bands, the name of Hofer is handed down to posterity in the annals of fame. Just when his country needed a guiding head and valiant arm, this hero started from his humble rank to rally the patriotic sons of Tyrol!“

Another woman, the poetess Louisa Stuart Costello, picks up the cause in 1846:

“ ‘Tis, as Hofer’s spirit woke,

he whose rifle freed the vales,

And in wailing accents spoke,

telling old, remembered tales.

Of the peasant hero’s fate,

Brief success and ceaseless fame,

England’s succour, all too late!

France’s vengeance, and her shame.“

Travel literature was influenced by all these works, with hardly any travelogue before the 1850s able to avoid the myth of the hero in the struggle for freedom. English-travel writers especially defined the historical and political image of Tyrol. The story of Andreas Hofer became the story of the desire for freedom of a people rising against tyranny.

After the initial euphoria, travel literature began in the second half of the 19thc. to describe the figure of Hofer in a more reserved and even critical manner, representing him as a complex personality containing both strengths and weaknesses. The depictions of the rebellion in travel literature and travel guides contributed to the myth from which the Tyrolean tourist industry has been profiting ever since: Tyrol became ‘Hofer Land‘.

John Murray’s 1855 Handbook for Travellers in Southern Germany looks in a more balanced way at Hofer the man.

“(Hofer) was naturally of a good-natured and kind disposition, and no act of wanton cruelty has been attributed to him during his whole career. (…) But his rashness on some occasions, and his weakness and indecision on others, were highly injurious to himself and the cause he espoused.“

Also published in 1855, ‘On Foot through Tyrol“ by Walter White reads as follows:

“Hofer, the Tell of Tyrol, is a hero about whom there is nothing mythical, as with his forerunner in Switzerland.“

He talks about how the “Passeyrthal is classic ground. Every step brought me to the birthplace of Hofer.“

He continues:-

“The struggle for freedom in 1809, with its fierce enthusiasm and heroic incidents, its triumphs and disasters, appeals strongly to the sympathies of all who hold liberty as their birthright. Let us, while pacing slowly along the banks of the darkening river, recall a few passages to memory.“

And he proceeds for several pages to retell the heroic struggle by referring to actual locations he has visited.

Turning to the fictional narratives written in 19th c. Britain, we need to pay tribute here to the pioneering research work carried by the late Professor Harro Heinz Kühnelt, former Professor of English Literature at the University of Innsbruck. He analyzed closely the historical novels about 1809: in particular –

Firstly,

Hofer, The Tyrolese, by Elisabeth Thomas (1824), where we read:

“…respected for his piety, his honesty and his loyalty…Hofer proved himself a man of singular modesty and humility…Wherever he appeared, the work of spoliation was stayed – whenever he spoke, his bidding was obeyed.“

Secondly,

The Year Nine: A Tale of the Tyrol, by Anne Manning (1858), which states:

“…Hofer had never endeavoured to ape a grandeur that he had not; he was a plain, simple, upright man from first to last. He had attained a great, though brief power, and had not abused it: he had fallen of it, but not into despair.“

And, thirdly,

The Tyrolese Patriots of 1809, by Diana Thompson (1859), which asserts:

“Never was a patriot moved by a purer and more disinterested love of his faith and of his fatherland.“

Such works were partly factual and partly fictional: these ‘factional’ works were often closer to historical novels than history books.

In the next article, we turn to 20thc. English travel literature about the Tyrol and Andreas Hofer.

von

von